Former Highway Tunnel Now Simulates Realistic Disasters

West Virginia facility trains emergency responders for calamities ranging from subway terror attacks to hazmat crashes

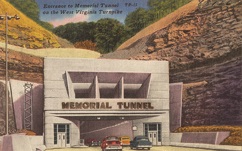

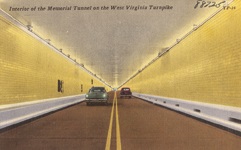

It’s 1954, and TV sets around the nation are tuned in to a news profile of the new West Virginia Memorial Tunnel. It is a high-tech marvel of its day, setting new standards for ventilation with its highly advanced system, and as the first tunnel in the country monitored by closed-circuit television. Thousands of highly reflective yellow tiles illuminate the passageway to reduce the cost of lighting, an innovation later adopted throughout the country.

Courtesy of Boston Public Library

A postcard shows the tunnel shortly around the time

of its opening in the 1950sIn its heyday, the tunnel, nestled high in the mountains near the tiny town of Standard, provided a vital connection along the West Virginia Turnpike between the cities of Princeton and Charleston. However, the construction of a bypass route in 1987 rendered the tunnel obsolete, and it was shut down. A few years later, a new purpose to address a pressing need—preparing for threats to national security—was found for the tunnel and the Center for National Response (CNR) was born.

The CNR is a unique multipurpose emergency response training facility, with organizations travelling from as far as Hawaii to train for a variety of threats and challenges. The tunnel is managed by the National Guard and is an element of the Joint Interagency Training and Education Center (JITEC). Customers include federal authorities, transit agencies, state DOTs, firefighters, local civilian first responders, urban search and rescue teams—even K-9 units.

Multiple venues are housed inside the tunnel, which runs more than a half-mile long and offers a confined area to set the stage for realistic emergency simulations.

“What we can do here in the tunnel is manipulate your senses, your sight, sound, smells,” said Air Force National Guard Lt. Col. Bill Annie, the CNR’s administrative officer. “We can make it noon, we can make it midnight, we can make it extraordinarily cold. We can pump in smoke and take away your sight. We have live role players come in screaming, ‘Help me! Help me!’ It is sensory deprivation—we can task out your senses to the point where you actually feel that you are in a disaster scene.”

Emergency responders assist a victim during a drill in the

Center for National Response Tunnel.When the tunnel was closed, it was initially used for storage and fire testing. Then in 1997, Maj. Gen. Allen E. Tackett, adjutant general of the West Virginia National Guard, recognized a strong need for a crisis management training facility and saw the tunnel’s unique potential to fill it. The construction of the CNR was timely, as terrorism was evolving into a worldwide threat. (The facility was established just nine months before 9/11.) Before then, the government didn’t view terror response in such a global sense—isolated domestic incidents were seen as a more immediate threat. Now, “The federal government has an interest in making sure first responders coast to coast are equipped with the same skills,” said U.S. Army Col. Mark Loring.

The tunnel transforms into a scene of terror to prepare response units for a real disaster, with the screams of paid actors echoing in the chamber, bloody dummies littering the ground, and giant fans creating gusty winds of 40 mph. The atmosphere of a true emergency is created in a safe, controlled environment. Despite the intensity of the simulations, carbon dioxide levels are monitored at all times to make sure oxygen is not depleted, and the CNR holds an impeccable safety record over the past 15 years of training.

“First responders come in with the facts of how to respond to a disaster, but it’s another thing to know how to respond and not freak out in a real emergency,” said James Acly, senior consultant with the defense contractor IIF Data Solutions, a supporter of JITEC. “Training is only truly testable when going through the stresses of a real incident, and you don’t want to find that out in the moment. Here, they can re-do the scenario if they don’t get it right. The whole training is only effective if they are able to respond instantly.”

Organizations have the ability to review their training sessions as cameras within the tunnel record the entire experience. Viewing the DVD as a team can strengthen group cohesion and allows the commander to point out areas for improvement.

Unique Capabilities

The CNR offers 10 setting options, including a subway, a stretch of highway, a collapsed building and a downed aircraft on the grounds outside the tunnel. Within these settings, teams have been trained to handle hazmat spills, severe crashes, improvised explosive device (IED) operations, hostage rescue scenarios and more. As the only non-active tunnel in the nation used for such training, the CNR is an ideal environment for practicing techniques to combat a weapons of mass destruction emergency in an underground highway or train tunnel.

A mock subway station inside the tunnel.

The CNR provides commanders with the ability to specify the conditions they want for their training while the CNR staff constructs the sets. With a staff ranging from retired civil support to Army technicians, the expertise is in place to produce almost any scenario a commander needs.

“What’s really different is there are lots of training venues across the country and everybody’s got a niche, but our niche is we can be whatever you want us to be,” Acly said. “Rather than us saying, ‘We have a fixed scenario where you can cut through concrete,’ we ask, ‘What kind of concrete do you want? How high?’ Whatever the circumstances, we’ll build it for you.”

The facility keeps its exercises up to date with issues affecting both local and national security.

“Whatever’s out there, whatever the latest version of IED, we are prepared for it,” Annie said.

After the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, the CNR was able to simulate the same type of bomb used. When the National Guard recognized vehicle rollovers as a significant threat to soldiers in Afghanistan, a mine-resistant ambush-protected (MRAP) armored fighting vehicle training course was created.

Workers take part in a hazmat exercise.

One source of national concern has been the expansion of transporting crude oil by rail, especially with high-profile derailment incidents in West Virginia and elsewhere making recent headlines. The facility is currently offering three- and five-day courses for emergency response to rail-related hazmat incidents. Additional scheduled events focus on responding to IED incidents on passenger rail lines.

Fully functional Chicago Transit Authority rail cars are used inside the CNR to simulate realistic incidents. Among the 10,000 acres of semi-wilderness surrounding the tunnel, old Boston Green Line cars are used for trail derailment exercises as well.

Parking garage collapse scenarios have also been popular with civilian first responders. In these exercises, units cut through concrete, save dummies and live role players, and push through obstacles.

A Well-Preserved Facility

For all that the tunnel has been through, from fire testing to bomb detection, its appearance remains remarkably intact. The original lettering above the entrance remains unchanged, and the architecture of the facility has a retro feel that harkens back to the 1950s, when it was built. The tunnel is under consideration for designation on the National Register of Historic Places.

Courtesy of Boston Public Library

A views of the yellow-tiled tunnel in a vintage

postcard.

“The whole building is the same thing all those people saw back in 1957 in their nine-passenger Country Ford Squires,” Acly said. “The care they took in making this art deco edifice is extremely well-preserved. It’s a neat little niche of historic turnpike building in our little tunnel in No Place, West Virginia.”

But, as evident from the cutting-edge technologies and unique capabilities of the CNR, the tunnel can be described with a list of adjectives beyond “neat.”

“We are more than just a tunnel,” Annie said. “We have 40 miles of driving trails, a training support facility where we can billet 97 personnel in bunks, an MRAP rollover [training area]. We have a shooting range, two helicopter landings. So yes, we are far more than just a tunnel.”

Hannah Chenoweth is a freelance writer based in West Virginia.