Eyes in the Sky Will Help Travelers Down the Road

Researchers see drones' potential for transportation management, emergency communications

Across the country, researchers are building high hopes for how data collected by drone aircraft can be used for transportation purposes. Although transportation agencies aren’t yet launching drones to handle their everyday work, experts believe it’s only a matter of time.

Recent tests have demonstrated the promise of drones for helping manage traffic, evaluating road and bridge repair needs, facilitating communications during disasters, informing emergency responders and more. In fact, a plethora of studies on transportation management is driving changes in drone design; software programs used to collect, store, and evaluate data; and methods of encryption to protect data streams.

NJIT

A team of researchers led by the New Jersey Institute

of Technology monitor a feed from a drone being flown off

Cape May, N.J., in January.“We see opportunities to use unmanned aerial systems in multiple ways, including maintenance, to inspect roads, road surveys, in con-struction, for emergency response, and in general photogrammetry [using photography in surveying to measure distances between objects],” said Gary Cathey, chief of the division of aeronautics at the California Department of Transportation.

Once perceived as a military technology, drones are now mainstream, sold everywhere from Amazon to neighborhood hobby shops. Private ownership of these aircraft—also known as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) or unmanned aerial systems (UAS)—has outpaced the creation of legislation to control their use, spurring the federal government to action.

In February, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) released a set of proposed rules for drones under 55 pounds conducting non-recreational activities. The regulations would limit flights to daylight, prohibit users from flying them out of sight, set height restrictions, and demand certifications for operators and registration for aircraft, among other operational parameters.

When the rules are finalized and take effect, likely between one and two years from now, they will ultimately allow more commercial uses for drones, including tasks related to transportation. Recreational operators, who must abide by separate model aircraft provisions, will be exempt. So will government agencies, which will continue to apply through the FAA’s Certificate of Waiver or Authorization (COA) permitting process.

A quadcopter drone used for recent tests in Florida.Federal statistics indicate the heightened interest in drones by government agencies, with the number of COAs issued nearly tripling from 2009 (146) to 2013 (423). Although there is a lot of controversy and discussion surrounding UAVs now, researchers have been experimenting with the devices for decades, according to Dr. Benjamin Coifman, professor of civil, environmental, and geodetic engineering at Ohio State University.

“Maybe eight years ago [my research team] had a demonstration project to look at the feasibility of using UAVs to monitor traffic and traffic-related issues,” Coifman said.

However, a great deal of work needs to be done on the policy side before UAVs can fulfill their potential, Coifman said.

“Are they accepted? What are the public’s perceptions of government? What is government using the data for? How long is the information going to be stored? The privacy questions are definitely big and they should not be ignored,” he said.

Monitoring traffic in Florida

Zhong-Ren Peng, professor of urban and regional planning at the University of Florida, has been experimenting with drones over the last few years to monitor travel speeds and behaviors at intersections and on highways and neighborhood roads around the city of Gainesville. Peng and a team of student researchers have monitored drivers, bicyclists and pedestrians passing the intersection of University Avenue and 13th Street, a busy area with unusual driving patterns near the main entrance to campus. The team also guided a UAV down a stretch of State Road 441 that claimed 18 lives in a multi-car pile-up in the rural Paynes Prairie area in 2012.

A still frame from video shot by a drone shows University

of Florida Professor Zhong-Ren Peng and a group of student

researchers as they prepare to launch the aircraft.“If we can capture an accident, we can do some predictions to prevent future, similar accidents,” Peng said. “We create models based on the data concerning traffic conditions and vehicle behavior to predict when a car accident is about to happen.”

Image processing programs automatically extract data from the videos, including the speed and volume of traffic, the numbers and times of lane changes, and the development of car-following behaviors of drivers. Peng’s group is currently working to improve the processing of images that the UAVs have captured.

“If a person is watching the video, they see the same things over and over. The eye gets tired,” he said. “Right now we’re working on getting a computer [program] to automatically identify traffic conditions and accidents.”

In China, Peng worked with a team of former students at Shanghai Jiao Tong University and the Shanghai Municipal Environmental Protection Bureau to study air quality using UAVs.

“We integrated mobile air pollutant sensors onto the UAV. The advantage of the UAV and mobile sensors is you can capture the air pollution in three dimensions and in larger geographic areas,” Peng said. “That, together with the land use on the ground and meteorological conditions will help us to better understand the sources and distributions of air pollution in China.”

NJIT tests show communications capabilities

In New Jersey, recent tests demonstrated drones’ reliability for relaying information clearly and from long distances during emergencies. Michael Chumer, professor of information systems at the New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT) and director of UAS research at the university’s New Jersey Innovation Institute, led a team in January that conducted three drone flights at the U.S. Coast Guard Training Center in Cape May. The tests were a joint effort between NJIT’s Crisis Communication Center, SRI International, American Aerospace Advisors and NC4.

Donald Shoup

A clear, consistent video generated by the NJIT drone was

successfully relayed from a van below to nine operations centers

in New Jersey and New York.The small single-propeller airplane-style drone was equipped to carry a mapping sensor, a communications relay device and a high-definition video package in its payload bay. The UAV monitored and mapped the shoreline while flying over the ocean, which presented the lowest crash risk. A camera fixed to its tail provided a continuous, streaming video of each flight, which allowed the pilot in command to see where the UAV was going.

“The output of the tail camera was fed to the Cape May Operations Center van, which passed that feed to eight other operations centers in New Jersey and one in Albany, New York,” Chumer said.

Each of the operations centers received a clear and consistent feed. The flights demonstrated that a single UAV has the potential to simultaneously convey to fire crews, law enforcement officers, EMTs and the media information on emergency events such as the size and severity of a multi-car pile-up, problematic road conditions, the weakening of a bridge, and dangerous conditions caused by weather. Technology aboard the drone could potentially allow it to serve as a “flying cell tower” when service has been knocked out and to provide real-time information to emergency responders during major storms like Superstorm Sandy.

Chumer said he came up with the idea for the flights three years ago while participating in a technology demonstration sponsored by the Naval Postgraduate School at Camp Roberts in Monterey, California. The group successfully streamed a lower resolution video feed from a UAV flying in military airspace to a ground station, which relayed the feed to a series of separate workstations.

Chumer said the clarity and consistency this time around was remarkable given the environment in which the flights took place. Heavy commercial air traffic generated by Atlantic City International Airport roughly 40 miles north could have crowded the radio frequency spectrum and interfered with the drone’s signal.

Creating rules of the road for UAVs

Drones may be able to monitor congestion on the roads, but their growing popularity could have them facing their own traffic challenges in the sky. That’s why Dr. Parimal Kopardekar is developing a traffic management program for drones at NASA’s campus in Moffett Field, California. The program, called the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Traffic Management System (UTM), will allow users to fly drones in a manner that minimizes the chances of congestion and collisions occurring in the air.

The overall approach calls for flexibility where possible, and structure—such as corridors, lanes and separation by altitudes—where absolutely necessary, said Kopardekar, manager of safe autonomous system operations for NASA.

Parimal Kopardekar, NASA

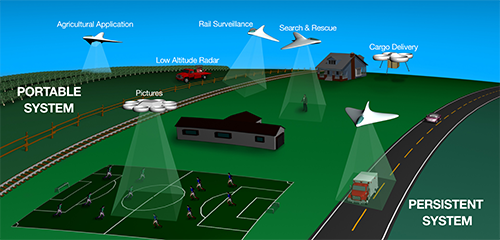

A NASA artist’s rendering showing some of the many civil and commercial uses of drone aircraft

in the future. “There are not going to be static roads. [Air traffic] is much more dynamic than that,” Kopardekar said. “If you have a density of a whole bunch of traffic, we see having one lane for agriculture, one lane for pipeline surveillance.”

NASA intends to use several different locations close to Moffett Field for test flights. The program has over a dozen research partners, both small and large. NASA is working with as many stakeholders as possible to conduct the tests.

The UTM project is organizing four flight demonstrations, tentatively scheduled 12 to 18 months apart. The first demonstration is set to take place in August.

Despite the excitement over the test flights, Kopardekar said the UTM team is focused on the development of software that will help manage the traffic safely. The program will be an online system with cloud-based data storage. It will need significant encryption protection to remain inaccessible to hackers.

Kopardekar said his team is interested in managing UAVs that go beyond the line of sight of the operator. The team is also looking at the effect of UAV noise as well as methods of controlling “rogue operators” who would seek to endanger people or property to cause havoc.

Addressing public reservations

A number of organizations are working to change negative perceptions of drones. It is important that the public not see them as dangerous machines, said Mario Mairena, senior government relations manager for the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI), a global nonprofit organization that promotes the use of drones.

“[The FAA does] not allow them to be weaponized. They’re going up for a specific scope and purpose to engage in a specific task,” Mairena said.

The economic potential of drones is a key selling point, according to Mairena. They are also lighter and therefore more cost-effective than helicopters or other small manned aircraft that would perform the same tasks.

“It usually takes between two and four folks to operate a UAS on the ground. UASs [are expected to] add over 103,000 jobs in a 10-year period. They will create high-tech, high-paying jobs that revolve around STEM [science, technology, engineering and math)-related initiatives,” Mairena said.

Keith Kaplan, CEO of the UAV Systems Association (UAVSA), a Beverly Hills, California-based non- profit organization that promotes UAV use and development, was at the White House for a discussion with staff from the president’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs on Jan. 26—the day a recreational operator crashed a quadcopter drone on White House grounds.

Kaplan said the crash stimulated discussion about a drone “pilot’s license.” The proposed federal rules would mandate operators pass an aeronautical knowledge test and obtain a certificate from the FAA.

Greg Principato, president and CEO of the National Association of State Aviation Officials (NASAO), said his organization has had to work toward relieving frustration and uncertainty even on the part of the FAA. He said the NASAO’s purpose is two-fold: to work with the FAA to bring order to how UAVs will be integrated into U.S. airspace and to serve as a facilitator for state governments to share information and best practices with one another.

Principato added that the main concern of the FAA and states regarding drones has been to develop “some good rules that provide safety and certainty so that this industry can grow.”

“[Almost] nothing new has happened in aviation since 1958,” he said. “UASs may be the first thing to come along to change that.”

Jessica Zimmer is a freelance writer based in California.