November 14, 2022

Alexandria Transit Company created a new network of routes and eliminated fares for DASH (Driving Alexandria Safely Home). dash

If science fiction movies are your guide, by 2022 you’d have expected to be living in some dystopian landscape: Machines becoming sentient, Harrison Ford chasing androids, Kurt Russell escaping New York. Thanks to The Jetsons, you’d think your commute would include a flying car. Or at least a measly jetpack.

Instead, commuting remains firmly stuck on the ground, often with only drones flying overhead taking cool photographs.

Nevertheless, the when, where and how of transportation and commuting has changed in dramatic ways. Two years into a global pandemic, some people are working entirely from home or going into an old-fashioned office just two or three times a week. According to the U.S. Census between 2019 and 2021, the number of people primarily working from home tripled from 5.7 percent to 17.9 percent. That’s 27.6 million people. In 2022, many of them have been gradually returning to offices but hybrid work is now favored by more than half of both employees and employers.

Employees may appreciate the newfound flexibility, but the trend has upended traditional commutes and with it, what transit agencies and transportation planners can expect in the coming years. Transit ridership hasn’t rebounded to the extent that car commuting has and that’s also likely to impact upcoming budgets, with shortfalls potentially impacting service.

For Philip Plotch, principal researcher at the Washington, D.C.-based Eno Center for Transportation, the more important question is what exactly is post-pandemic? “When is the new normal kicking in?” Surveys of employers are consistently overestimating how many people are coming back and how often. “Agencies are a little skeptical of the numbers because employers have been a little overly aggressive,” he said. “There’s so many question marks out there,” about the state of the pandemic, with variant spikes every few months, but also the state of the economy.

Transit agencies in general received significant federal funds to make up operating gaps during the early part of the pandemic but it’s unclear how that’s going to work in the next few years, said Yonah Freemark, a senior research associate, and lead of the Fair Housing, Land Use, and Transportation Practice Area at the Urban Institute’s Metropolitan Housing and Communities Policy Center. “It’s a major concern, actually.”

What’s become increasingly apparent with the job market and inflation is that it’s going to continue to be very hard for transit agencies to maintain their operations. “That’s going to be a major issue,” Freemark said. “The effects of inflation are going to make it very difficult to pay for basic services.”

DASH (Driving Alexandria Safely Home) went fare free in September 2021 after examining other options, including free or half-price fares for low-income residents only. dash

There’s a real concern that transit agencies may cut service, Plotch said. Agencies with the lowest fare recovery ratios require the most subsidies and the ones that traditionally have the highest ratios are most susceptible to ridership losses, he said, adding that frequency of service is key, especially in areas like New York City where transit usually competes very well with people taking cars. Ridership numbers are more resilient than other parts of the country because traffic is bad, and the cost of driving is high. But if agencies start cutting service, whether late at night or every 30 minutes instead of every 10 minutes, that ends up reducing the number of people using the system.

“Transit is competing with all these other modes,” Plotch said. “Operators have to figure out what their strengths are and their market niche; what amenities and services they have to make them compete better.”

Agencies Respond

Transit agencies have rolled out discounts to try to boost ridership while some cities have experimented with new concepts and products like microtransit. After a two-year hiatus, ride-hailing company Uber is bringing back its ridesharing program, which Plotch thinks is a big deal. “I was afraid they were going to give it up.”

NJ TRANSIT in February 2021 launched FLEXPASS, a 20-trip ticket discounted 20 percent off the one-way fare, geared toward commuters on a hybrid work schedule. As of September 2022, 350,000 passes have sold.

Freemark is optimistic that some transit agencies are trying to be responsive to different types of travel needs. “There’s a lot of people who might have different desires than the destinations they used to; especially to other neighborhoods and not downtowns,” he said, and there are agencies that want to respond to that. At the same time, he fears there’s “a bit of status quo” at transit agencies. “They’re used to providing the services they provide. It’s hard to get them to change that approach.”

The Greater Richmond Transit Agency is among several agencies that went beyond just discounts by eliminating fares entirely. It also reoriented service to local bus routes to prioritize essential workers and social equity. “It speaks to a broader need to improve,” said Freemark, who was among the authors of On the Horizon: Planning for Post-Pandemic Travel, a study released late last year by the American Public Transportation Association (APTA). It presents five case studies of transit agencies’ responses to the pandemic. “The experience to me does suggest that free fares can be an effective way to keep people on transit,” he said.

Ridership on Alexandria, Virginia’s DASH (Driving Alexandria Safely Home) returned to pre-pandemic levels since implementing free fares and new routes. dash

Elsewhere in Virginia, the Alexandria Transit Company’s DASH (Driving Alexandria Safely Home) went fare free in September 2021, after examining other options including providing free or half-price fares to low-income residents only. It also created a new network of routes. The results have been dramatic. In May 2021, monthly ridership was only about 45 percent of pre-COVID levels, but since implementing free fares and new routes, ridership is back to pre-pandemic levels.

Like other transit agencies, the largest growth in ridership on DASH has occurred during what used to be non-rush hours — middays, evenings and weekends—surpassing pre-COVID ridership during those times. As more commuters continue to return to the office, DASH expects ridership will continue to increase, according to Whitney Code, marketing and communications manager.

Not surprisingly, the biggest challenge to going fare free is how to make up for lost revenue. “For agencies with less support, it is important to highlight the benefits for free fares for the entire community with increased bus ridership. More people on buses means less traffic, less parking demand, less environmental degradation, a stronger local economy, and better overall quality of life.”

Prior to the pandemic, Alexandria’s DASH averaged about $4 million in annual fare revenue. To defray the lost revenue, the agency was budgeted $1.5 million by the city in 2022 and was awarded $7 million over the next three years by the state of Virginia. DASH expects to remain fare-free through FY2025.

Another challenge has been ridership data collection. Since DASH went fare free, customers no longer tap a SmarTrip card to get on the bus, which means no more data on rider types, fare media, or transfers, which are useful to the agency for planning. Instead, bus operators manually enter the number of passengers boarding until automated passenger counters are on board later this year.

Legislators in Ulster County, New York, about 90 minutes north of New York City amid the Catskills, in August approved free fares on its county transit service effective October 1—after some opposition among members.

In preparing a plan for free fares or reduced fares, Deputy County Executive Christopher Kelly said the county had to “work through some of the different scenarios to ensure we don’t impact our ability to claim state/federal reimbursement” which is based on farebox recovery. This included gaining approval from the Federal Transportation Administration.

Ulster County will pay for each individual trip through its general fund, counting each bus rider to maintain an accounting so there’s no negative effect on state or federal aid, Kelly said, adding that the county plans to review the scheme in its annual budget cycle.

“At this point, we may pursue private funding or somehow tie in our bus advertising to pay for ridership, but I think we have a lot to learn before we go down that road,” Kelly said via email.

Ulster County Area Transit (UCAT) eliminated $1.50 fares on its buses and adjusted routes, effective October 1.

“In a sense, the revenue won’t be lost because we anticipate the state will continue to return $3 to us for every $1 we send them from fares that the county will now subsidize rather than riders paying,” said Legislator Phil Erner, a co-sponsor of the measure. Fare-box revenue has decreased every year—from about $400,000 in 2015 to $342,000 in 2019 and continued to drop amid the pandemic the past two years—on an operating budget of about $7 million. “Spread across the whole county, it’s really pocket change, which our poorest residents now won’t have to worry about.”

Free fares aren’t for all. Agencies in Spokane, Washington, and Denver, Colorado, found that fare-free travel encouraged homeless people to keep their belongings on transit, according to the APTA study. Philosophically, some transit boards believe riders should contribute to the cost of the ride.

There’s no one clear answer when it comes to free fares, according to Freemark. It’s difficult to envision a future where transit is free in large cities like New York, Boston and Washington, D.C., where fares make up a huge share of the overall costs for transit agencies, which would have to find billions of dollars to make up the gap.

Ridership Hasn’t Returned

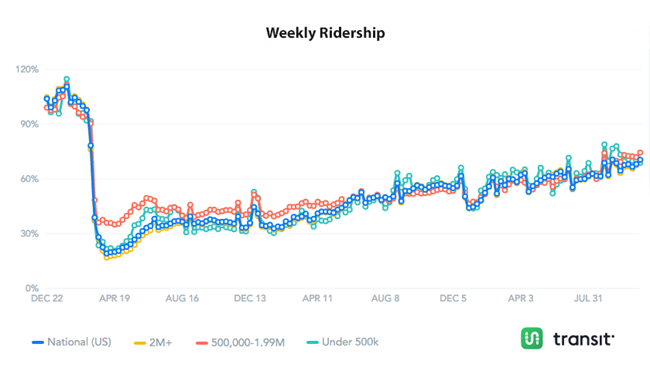

Transit agencies in general still haven’t returned to pre-pandemic ridership levels. Ridership among smaller agencies (less than 500,000) has rebounded somewhat better than at larger ones but even their peak has only reached about two-thirds of what it was before the pandemic as recently as July, according to trends tracked by the APTA. Though ridership has slowly climbed, even eclipsing 70 percent as recently as September, it could retreat in the face of another COVID variant as it did in the past, according to APTA.

That may not necessarily be the case for commuting patterns by car. The APTA study suggests that driving quickly returned to normal. Figures from the agency that operates the world’s busiest bridge confirm that. The number of automobiles crossing the six bridges—including the George Washington Bridge—and tunnels operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey plummeted to 3.4 million. That’s almost a third of the average 9.3 million cars per month during 2019. Volume returned to the 9-million mark in May 2021 and has continued.

The American Public Transportation Association tracks weekly ridership on transit systems going back to December 2019.

Some traditional commuting patterns on transit re-emerged as early as this spring. According to Fred Nangle, deputy director of service planning projects at MTA Metro-North Railroad who spoke at Metropolitan Area Planning Forum’s June meeting. The peak morning rush of 7:30 to 9 a.m. and Tuesday-Thursday peak of the week curves have reappeared, with hybrid workers clearly working at home on Fridays.

Metro-North reinstated peak fares on non-commutation tickets as normal commuting patterns have begun to reassert themselves but now—like NJ TRANSIT—also offers a discounted 20-trip ticket aimed specifically at hybrid workers. Weekday ridership has returned to more than 50 percent of pre-pandemic as the Omicron variant faded, and more recently to about 55 percent.

Ridership on NJ TRANSIT is about 55 percent of pre-COVID levels overall, but weekend service has seen a rise, from about 80 percent to 90 percent with some trains at 100 percent, President and CEO Kevin Corbett said during the board’s June meeting. Interstate ridership into New York is at 65 percent and intrastate ridership within New Jersey is at about 75 percent.

If people are still apprehensive about taking mass transit and wary of high gas prices to jump in the car, maybe other options will emerge?

Citi Bike, New York City’s bike share program, saw 92,300 daily trips in May 2022, up 45 percent from May 2019. Part of that growth was the expansion from 777 stations in 2019 to 1,548. All those figures continued to grow as of July with each bike used an average of 4.13 times per day.

Across the Hudson in Jersey City, New Jersey, Citi Bike experienced the smallest drop in ridership during the pandemic compared with other options, according to JC on the Move, a study exploring innovative and emerging transportation modes to address service gaps in New Jersey’s second-largest city.

It’s not exactly a jetpack or flying car but a recent Bloomberg report looked at how bikeshare programs stepped in when transit systems were down, citing a North American Bikeshare and Scootershare Association study that “bikeshare systems can help boost transit ridership when they’re better integrated.”

Mark Hrywna is the editor of InTransition magazine.