November 14, 2022

Only two electric vehicles sold 100,000 units or more in 2021: The Tesla Model 3 and Tesla Model Y. Tesla

The end of the road for the internal combustion engine car arrives in 2024.

According to the BloombergNEF Long-Term Electric Vehicle Outlook 2022 (EVO), published in July, the global fleet of gas-guzzling passenger vehicles will grow for the next two years before entering a permanent state of decline. The slide is virtually inevitable. Where government subsidies were once critical to sustaining the industry, the report concludes that the U.S. is nearing the point where consumer demand will take hold of the wheel.

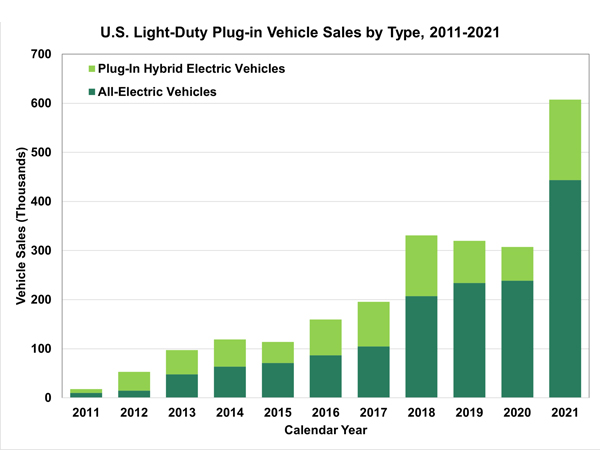

A growing body of data has begun to demonstrate the change underway. In the years preceding 2020, the market share of electric vehicles (EV) sales hovered in the 2 percent range. In 2021, it more than doubled to 4.7 percent, from 325,000 vehicles sold in 2020 to 657,000, according to Corey Cantor, co-author of the EVO.

And while 14 of 15 major automakers saw year-over-year losses in a Cox Automotive Industry Insights comparison of first half sales in 2021 vs first half sales in 2022, one saw an increase: Tesla. On average, the 14 absorbed a 17 percent sales loss; Tesla sales rose 89 percent.

“It’s still a relatively small part of the market at 5 percent, but it’s where all the growth is,” Cox Director of Corporate Communications Mark Schirmer said. “We expected this to be the EV decade.”

Changing Perceptions

So far, the decade belongs to Tesla. According to Cantor, only two EVs sold 100,000 units or more last year: The Tesla Model 3 and the Tesla Model Y. The next best seller was the Ford Mustang Mach-E SUV, at about 30,000 units.

Part of the gap can be attributed to Tesla’s deft navigation of the supply chain issues that have badly slowed the manufacturing capacity of automakers across the board. It is perhaps also a matter of changing tastes.

Where the notion of driving an EV once conjured the stereotype of a liberal environmentalist in a Toyota Prius, Tesla is regarded as something entirely different: a status symbol. Its drivers are less green-minded activists and more the tech lovers who’ll wait on lines for the newest iPhone.

“The Tesla phenomenon was built more on early tech adopters and not hardcore green adopters,” Schirmer observed, pointing to its overall performance and famed tech features that set it apart from other cars. “Tesla is the #1 luxury vehicle nameplate now in the U.S. It outsells Mercedes and BMW and Lexus. It’s not just the #1 EV, it’s the #1 luxury vehicle maker in the U.S., so a real success story.”

Dumping the Pump

It hasn’t hurt the EV’s cause that Americans are suffering through the worst gas prices in history. As average prices climbed above $4 and finally above $5 per gallon in the spring, Schirmer said two Cox properties, AutoTrader.com and the online Kelley Blue Book, saw searches for EVs surge.

A June poll by AAA indicated that gas prices have nudged drivers who may have had reservations about EVs to get off the fence. A quarter of those surveyed said they would be likely to buy an EV for their next auto purchase, with Millennials leading all groups at 30 percent. The top reason cited was to save on fuel costs (77 percent).

If half of all vehicles sold by 2030 were electric, which is the current federal target, the U.S. would need about 20 times more publicly available charging stations than currently exist. Tesla

“The increase in gas prices over the last six months has pushed consumers to consider going electric, especially for younger generations,” said AAA Director of Automotive Engineering and Industry Relations Greg Brannon. “They are looking for ways to save, and automakers continue to incorporate cool styling and the latest cutting-edge technology into electric vehicles, which appeal to this group.”

But therein lies the paradox. At a moment when exorbitant fuel costs and supply chain shortages have convinced a whole new crop of buyers to kick the tires on an EV purchase, they’ve found there are few to none to be had, thanks to those same problems. “These people are interested in electric vehicles but they’re not necessarily buying them yet and the reason is, they’re just not affordable enough on the upfront base,” BloombergNEF’s Cantor said. “But it has planted a seed in there.”

Prices Remain a Barrier

In June, prices for new autos of all stripes hit an all-time high, with severe inventory shortages inflating prices, according to Kelley Blue Book estimates. The story was no different for EVs, which rose to an average sale price of over $66,000. The availability of various models has differed from region to region, but long waits are the norm.

The competition for the limited supply of inventory even gave rise to an automotive version of the ticket scalping industry. A June story in the Los Angeles Times profiled a new breed of “EV flippers” who advance order autos like the Tesla Model Y and Rivian R1T electric adventure vehicle, offer them at a steep markup on sites like Facebook Market, and find willing buyers with little problem.

It won’t always be this way, experts promise. Every major automaker has its own variety of EV models in their pipelines, ready to launch in the coming years. Many of them will be affordable alternatives to Tesla and the other luxury EVs.

Today, the Hyundai Ioniq 5, Kia Niro and Kia EV6 sports utility vehicles are drawing strong reviews and slowly growing in volume. Their starting prices are in the neighborhood of $40,000, which is still a tough sell for consumers looking for an affordable car. But that cost can be brought down to the low $30,000s with a combination of rebates and incentives offered by some states and the federal government through President Biden’s recent Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) legislation. Likewise, advances in battery technology, automakers continued scaling up in production, and the gradual clearing of supply chain problems are expected to cool prices down.

By 2030, BloombergNEF projects 44 percent of vehicles sold in the U.S. will be EVs, with adoption uneven from region to region (California is already at 17 percent now). At the end of the 2030s, American drivers looking at the cars surrounding them on the highway can expect to see more EVs than internal combustion engine vehicles.

Infrastructure Challenges Ahead

Are American roads ready? An analysis by McKinsey & Company concluded that if half of all vehicles sold by 2030 were zero-emission EVs, which is the current federal target, America would need about 20 times more publicly available charging stations than it has now. Similarly, the EVO estimates the U.S. will need six times as many stations deployed four years from now than it has today. Even with the $7.5 billion allotted through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to spread 500,000 public chargers across the U.S., the country would be well short.

The market share of electric vehicles sales more than doubled to 4.7 percent in 2021, with some 657,000 sold in the United States. U.S. Department of Energy

Cantor believes utilities and the private sector will need to step up and play a greater role in helping the U.S. meet the demand. He added that not all of the charging stations need to be of the fast-charging levels, but they do need to be reliable, so investment in their upkeep is another necessity.

“The good news is, there’s still time for folks in the private sector to get ahead of it,” Cantor said. “There’s always a bit of the chicken and the egg element to charging infrastructure.” There is no longer any question that the egg is hatching, though. The EV, for so long an idea that Americans expected to manifest at some vague point in the future, has begun its ascendance as the industry standard.

“A couple of years ago we’d be having conversations and folks would say, ‘Do people really want electric cars? Do they have enough range?’” Cantor said. “And now the question is more, are automakers going to ship enough to meet demand? And when will we get back to that equilibrium point of having to wait only a couple of weeks, or even walking off the lot with one, versus waiting three to six months for some of the cheaper models?”

Karl Vilacoba is the Communications Director for the Monmouth University Urban Coast Institute.