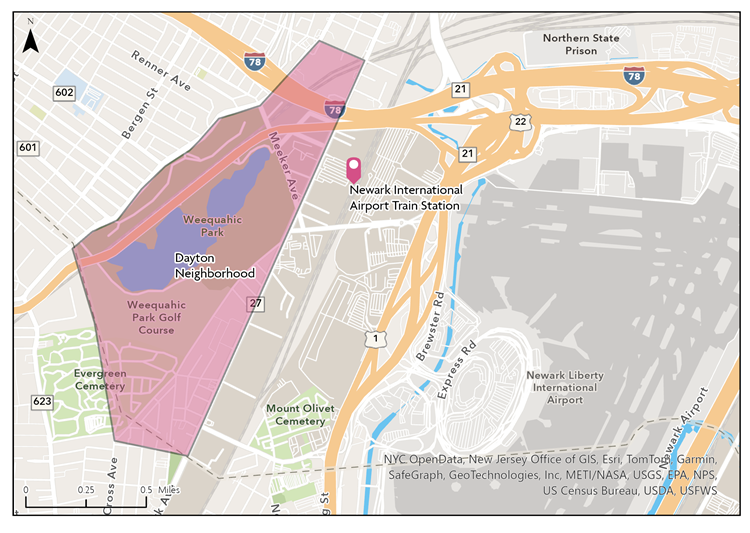

FROM ALMOST ANYWHERE in Newark’s Dayton neighborhood one can see the train station serving Newark Liberty International Airport, the nation’s 13th largest in passenger traffic. But for residents of this neighborhood, part of Newark’s South Ward and one of the city’s most economically challenged, residents have no direct access to the busy station. Not only are they walled off from using it for their own travel needs but they have little opportunity to reap economic benefits, in terms of commercial or other development, from the thousands of weekly air travelers passing through.

If they try to access the station on foot, Dayton residents encounter a chain link fence; if driving, a locked gate blocks passage. And if they succeed in avoiding these obstacles and reach the building, they will find the doors locked.

But almost 25 years later, in late 2026, the train station at Newark Liberty International Airport is slated to finally open a new door to the public. This will allow Newark residents and many others the opportunity for the first time to board the AirTrain directly from their neighborhood and not have to travel to downtown Newark first. From this station they will also be able to step onto a train for New York City or Trenton or beyond, opportunities which will enrich the lives of many, especially Newarkers. And with the help of a coalition led by the City of Newark, grand plans are taking shape to use access to the station as a catalyst to bring new development and jobs to Dayton, one day possibly making the area a centerpiece of a thriving “Aerotropolis” of linked housing, businesses and the commercial services tied to aviation.

Since it opened in 2001, Newark International Airport Station along the Northeast Corridor line has been restricted to passengers arriving by train. Acroterion

As a professor of architecture at the New Jersey Institute of Technology in Newark, I have been privileged to take part in the coalition and its effort. This article recounts how the coalition achieved the breakthrough in station access and has been paving the way for a new future for the Dayton neighborhood and the larger city. It is a story of effective local organizing and persistence that has lessons for other communities seeking to grasp new opportunities.

The Station

The Newark Airport station is located on the Northeast Corridor rail line, the busiest passenger rail line in the United States by ridership and service frequency. Passengers arriving at the station on Amtrak or NJ TRANSIT trains reach the airport terminals via AirTrain, a monorail serving 33,000 riders each day, with other stations at airport parking lots. The airport and monorail are owned and operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

As New Jersey’s largest city, Newark has a population of just over 300,000 and is a key transportation hub for both people and goods. In addition to the airport, Newark is home to the largest marine container port on the East Coast and is served by the New Jersey Turnpike and other major highways. Newark Penn Station is served by high-speed regional rail, major commuter lines, light rail, buses, and is the terminus of the PATH train system operated by the Port Authority.

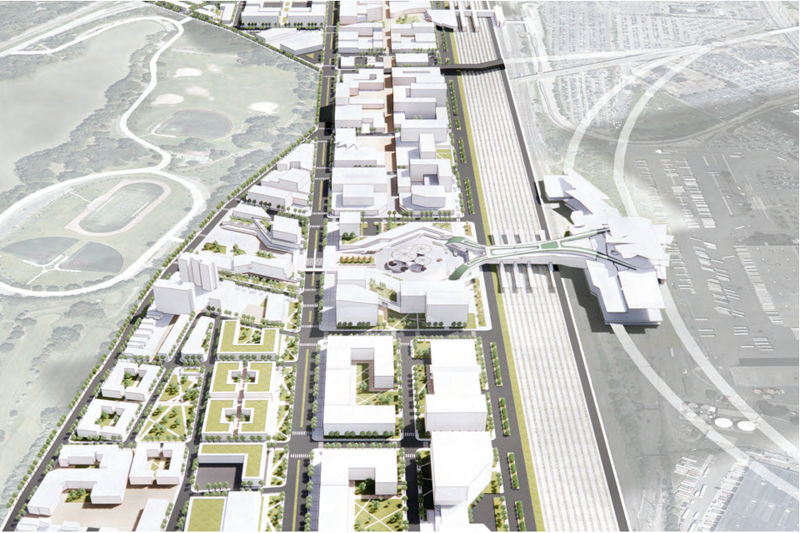

The EWR Headhouse and Train Station creates an architectural feature in the middle of the site, where the public realm extends inside and creates a more connected and high functioning airport and transit facility.

Despite this extensive rail service in and around Newark, Newark Airport created in 1928 lacked rail access for decades. That finally changed in 2001 with the opening of the Newark Airport Rail Station. It was hailed as giving Newark Airport the same rail access as other major airports. But to many residents of Newark, the opening was the source of frustration and anger due to the lack of access

The Coalition

The effort to overturn barriers to airport station access from the Dayton neighborhood dates to 2017 when Newark’s Ras Baraka administration tapped several stakeholders, planners, and academics to form the

Airport City Newark Coalition (ACNC).

On the academic side, the co-chairs (known as “co-principal investigators” in academese) were

NJIT’s Dr. Colette Santasieri and me, with University of Pennsylvania’s Marilyn Taylor, and Rutgers University’s Barbara Faga playing critical roles in support. The coalition would be later joined by Dayton resident Isaiah Little who has led outreach. Over the years, many others have been part of coalition activities and discussions, including then-Newark Planning Director, Christopher Watson. Pallavi Shinde, the new director, has taken on this essential position.

After many campaigns, with significant setbacks, the coalition’s doggedness ultimately accomplished what Mayor Baraka sought: In March 2023, the Port Authority promised to open the station, pledging $12 million for its design.

In response, I told the Port Authority’s governing body:

Today we applaud the Port Authority for beginning the planning process to open the Newark Airport Train Station and urge the commissioners to vote in supporting it. Opening the station is an historic decision that corrects a social wrong, one that has prevented Newark residents from accessing a station in their own neighborhood, all because of a poorly crafted federal law.

Priorities

When formed in 2017, the coalition’s mission was to organize Newark communities to provide input toward a then-planned PATH train extension to the airport station. The extension would solve the access problem because PFCs would not be used and thus no restrictions on its use would apply. The extension was to include a station on the edge of the Dayton neighborhood.

While the PATH extension was identified as a priority in the Port Authority’s capital plan, by 2019 another pressing priority was looming. The AirTrain monorail was increasingly showing signs of age, experiencing service interruptions due to accidents, power failures, and maintenance. Ultimately, the Port Authority determined that it had reached the end of its useful life and needed replacement. The agency could not afford both. A PATH extension that was so close at hand was put in limbo as work on an AirTrain replacement proceeds with a 2029 projected opening date.

By the time of the cancellation, the coalition had received the first of a succession of grants from the Prudential Foundation to support outreach activities focused on the opening of the airport rail station. The cancellation brought about a pivot to research other issues. These included better understanding the opportunities a station on the busy Northeast Corridor, one 30 minutes from Manhattan, could offer as a Transit Oriented Development (TOD) opportunity.

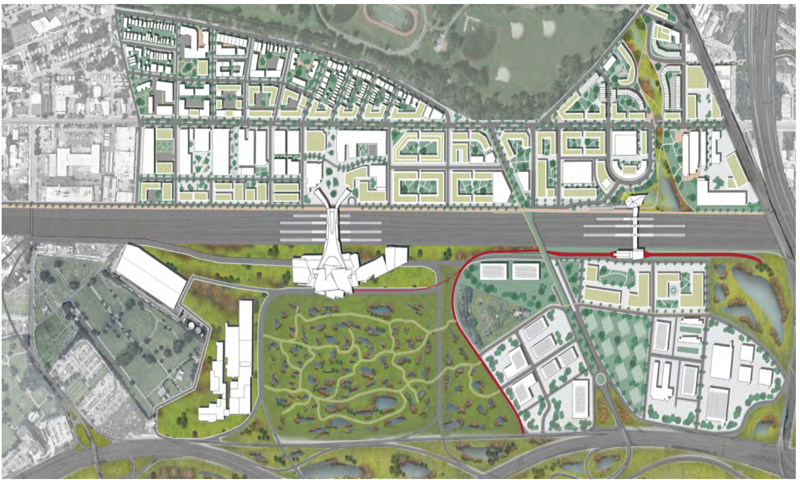

Generate Newark 2050 takes a larger scale approach to generate a new urban and natural landscape that embraces its ecological heritage, while providing more green spaces and trails that connect the South Ward to both the Newark Bay and Downtown Newark.

A typical TOD promotes mixed-use development around rail infrastructure. The coalition sought to overlap the well-understood rail TOD with one focusing on aviation, applying the Aerotropolis concept recently developed by John Kasarda and Greg Lindsay in their eponymous book. These authors contend that airports will be to the 21st Century what train stations had been to the early 20th, with new urban formations growing from airports, reflecting the promise of global communication in the new century.

Many coalition members knew of the Aerotropolis concept and had already considered it in their advocacy for reimagining Newark Airport. Primarily through their association with the

Regional Plan Association (RPA), several coalition members had focused extensively on Newark Airport.

In its

Newark Draft Vision Plan for the newly-arrived Booker administration in 2006, the RPA identified the airport rail station area as a potent location for redevelopment. Shortly afterward, the Port Authority commissioned the RPA to assess the metropolis’ future aviation needs. The study group found that for the region to remain globally competitive, it would require two new runways, either at JFK or EWR. These findings were published in the

2011 Report, Upgrading to World Class, with amendments issued as part of the RPA’s

Fourth Regional Plan.

Proposals for bringing in new modular affordable housing, renovating existing schools, redesigning Frelinghuysen Avenue, and creating a new signature plaza connecting the Dayton District to the new EWR Headhouse focus on creating short-term improvements that set the scene for larger infrastructure changes.

Building upon the RPA recommendation to add to and reorganize the runways, the coalition proposed a vision for a new central terminal atop the Northeast Corridor, known in aviation parlance as a headhouse. This vast building, modelled after Amsterdam, Singapore, and Hong Kong, would connect via underground people-movers to midfield concourses adjacent to an expanded runway apron. A new airport configuration could then promote a Newark Aerotropolis that by UPENN estimates could repurpose up to 300 acres, create 20,000 to 25,000 new jobs, and provide 10,000 to 12,000 new inclusionary and workforce dwelling units to house 13,000 to 16,000 new residents.

The coalition mobilized its university partners to host architectural and urban design studios to not only design new terminals but also a comprehensive aerotropolis surrounding them. And although the FAA increased its runway clearance requirements while design was underway, lessening the need for additional runways at Newark, these proposals have been widely publicized with several winning awards.

Rendering of interior of future Newark Airport Headhouse.

Parallel to this effort, other team members performed other necessary tasks: inventorying the brownfields surrounding the airport, predicting the impact of sea level rise, and anticipating how autonomous vehicles might change airport access. Most important, the coalition held dozens of meetings with community members to carefully gauge support (or disapproval) to any airport expansion.

In the eight years the coalition has been operating, it has assembled a well-informed and interested group of community advocates from which it regularly seeks counsel. In April 2021, the ACNC incorporated this group into an international online conference that brought the leadership of the world’s two largest airports, Atlanta and Amsterdam, to participate in a day-long assessment of the opportunities at Newark.

At the conference, former Atlanta mayor Shirley Franklin praised Newark’s community involvement, explaining its importance: “There are many people who talk about how important leadership is and leadership certainly counts, but so does ‘followship.’…stakeholder outreach is as much about followship as it is leadership.”

The coalition's advocacy earned it seats on related efforts. The Port Authority invited four members to join a Technical Advisory Committee to study

Newark Airport’s future reconstruction and Mayor Baraka asked coalition members to serve on the steering committee for the

Newark 360 Master Plan, which placed great emphasis on the airport as a driver for the city’s future. The Newark Master Plan and accompanying ordinances were a major success and recently received the 2024 Daniel Burnham Award for a Comprehensive Plan from the American Planning Association.

Illustrative plan of Newark Airport and vicinity, including Weequahic Park, Frelinghuysen Avenue, and Regional Greenway.

Early on, the coalition recognized a gap in support it could not provide: An economic assessment of the viability of development around an airport is essential in attracting support and investment. The quality of these studies is reliant on access to market data that only private consultants, and very few universities, have up-to-date access to. To fill this gap, the coalition applied for support from the U.S. Economic Development Administration, with a match grant from the N.J. Economic Development Authority (NJEDA), to solicit for proposals for this service. The coalition selected the firm Hatch International because of their real estate analytic capacity but also because of their understanding of the global Aerotropolis phenomena.

Hatch not only interviewed innumerable stakeholders and local officials, it also carefully assessed various sectors in the real estate market for northern New Jersey to predict the viability of airport development on approximately 40 acres surrounding the soon-to-be community accessible station. They developed both community-focused and market-focused scenarios as well as a hybrid one to present a viable mixed-use arrangement. And based on a study of comparable airport developments in the U.S., the team also found Newark airport to be underserved by hospitality, with a need for as many as 1,000 additional hotel beds in airport adjacent facilities.

The

Hatch Report proved to be the missing link the coalition expected, adding to the anticipation about the benefits that could be realized with the community-accessible train station opening in 2026. The NJEDA has pledged further support for the City of Newark for redevelopment planning for the station environs.

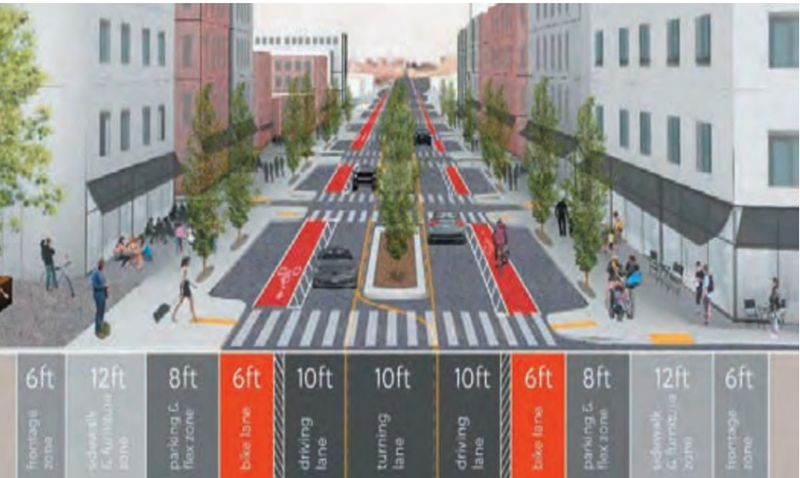

Frelinghuysen Avenue would be slimmed down and the street wall would be enhanced and built out to create a more livable and human-scaled street.

As it continues its efforts on many fronts, the coalition seeks to integrate other developments into its efforts to build a stronger community. These include the Lionsgate film studios nearby as well as a rethinking of Frelinghuysen Avenue as a complete street. The coalition will also continue to work to develop Community Benefit Agreements that serve as a rider to redevelopment legislation declaring a community’s needs, as well as examine the opportunities opposite the planned development for the vast surface parking lots adjacent to the airport station to the southeast. And finally, the coalition will provide a thorough technical review for any construction ordinances that would need to apply to aviation-adjacent structures to ensure acoustical livability.

The opening of the Newark Liberty International Airport Station to the Dayton neighborhood indeed marks a milestone that culminates a sustained effort by the Airport City Newark Coalition. In many ways, however, it is more intermission than finale as there is much to be done to have the planted seed that is the opened station blossom into a full-blown transit-oriented development focused on aviation. The provisions of the Port Authority’s new access point are rudimentary, with much of the apron facing Frelinghuysen Avenue covered in asphalt. Yet this is seen by the coalition and its community partners not as an end but a clean slate to envision a future community yet to be built.

Darius Sollohub is a Professor and Interim Chair of the School of Architecture in the Hillier College of Architecture & Design at the New Jersey Institute of Technology.