As Gas Tax Loses Power, Fees Closer to Reality

Innovative Programs at State Level Show Potential Ways Forward

Ed Murray

August 1, 2023

THE ICEBERG IS approaching. The tank is nearing empty. Choose any analogy you want, but the fact is clear: The gas tax, long the primary mechanism for funding surface transportation at the state and federal levels, is rapidly becoming obsolete.

Fuel tax revenues are being strained by a pair of market forces that are good news from an environmental perspective. First, passenger vehicles are far more fuel-efficient today than even a few years ago. In

a May presentation to the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council,

Eastern Transportation Coalition Director of Innovation Programs Virginia Reader estimated that a 2009 Toyota Camry consumed 25 miles per gallon (MPG) and contributed an average $278 annually in fuel taxes to Pennsylvania. A 2019 Camry owner would get 52 MPG and pay only $134 for driving the same distance.

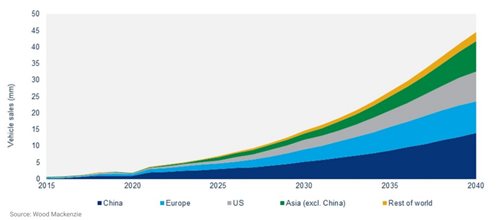

Second, electric vehicles (EV) are

beginning to take to American roads in high numbers and are projected to surpass internal combustion engine car sales in the 2030s. Their owners pay no gas tax at all.

In short, cars are putting a greater pounding than ever on roads and bridges, but paying less for their upkeep. Yet no one seems to be particularly worried about it.

In 2013, RAND Corporation

In 2013, RAND Corporation Senior Policy Analyst Liisa Ecola and a team of researchers published “

Mileage-Based User Fees for Transportation Funding: A Primer for State and Local Decision Makers.”

The report was intended to offer guidance to government agencies interested in starting a transition from the gas tax to a mileage-based user fee (MBUF) or vehicle miles traveled (VMT) fee structure. Looking back a decade later, Ecola said she would have expected at the time that at least a small number of states would have made a clean break by now. None have.

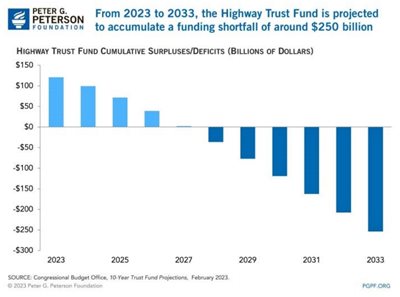

“It’s the irresistible force meeting the immovable object,” Ecola said. “People might think it’s inevitable that we have to switch to a different system because of vehicle electrification, but there’s never the political will to do it, and I don’t have a good sense of how many more crises with the federal highway trust fund it will take before people look at this as a solution.”

PILOTS LIFT OFF

However,

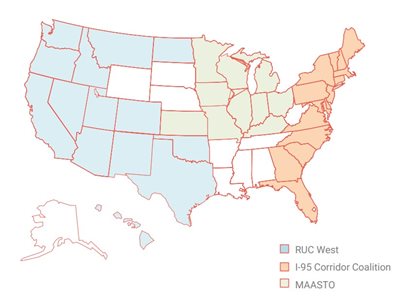

However, MBUF proponents see promise in the number of pilots that state and local governments are conducting around the country. Roughly half of U.S. states are currently or have been engaged in a pilot program, according to Barbara Rohde, director of the Mileage-Based User Fee Alliance (MBUFA), a nonprofit dedicated to education and outreach on MBUFs and improved performance of the U.S. transportation network.

The pilots are taking varying approaches to everything from how mileage is reported or collected, to how much drivers are charged, to how to recoup costs from out-of-state motorists. Rohde believes the state experiments are producing important lessons on what works and what doesn’t, and eventually, a subset of the best ideas will emerge.

“All of these pilots have shown us how important it is to focus on regional approaches, because this country is very big and diverse,” she said. “What works in Florida might not work in Washington State. What works in California might not work in Michigan. What they don’t want on the Hill is what we saw with the tolls, which was a patchwork quilt around the nation, with E-Z Pass here in the East and another one in the Midwest that’s not compatible with the South.”

Federal investments are incentivizing state and local governments to play their roles as laboratories of policy. In 2014, the Federal Highway Administration

Federal investments are incentivizing state and local governments to play their roles as laboratories of policy. In 2014, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) made $95 million available for six rounds of Surface Transportation System Funding Alternatives Program grants for MBUF pilots. Last year’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) provides another $125 million – $50 million of which will be used to conduct a national-level pilot, and $75 million to be distributed competitively to states, local governments, regional partnerships, and metropolitan planning organizations.

PERMANENT PROGRAMS

To date, four states have gone beyond pilots to enact MBUF programs that are permanent, although limited in scope. Participation in the first three listed below is voluntary for the moment.

- Oregon: The nation’s oldest MBUF system debuted in 2015 and currently has 800 EVs, hybrids and natural gas-powered cars enrolled in the program. OreGO participants pay 1.9 cents per mile traveled and the system has no fee cap, meaning the more that vehicle owners drive, the more they will continue to pay.

- Utah: The state’s Road Usage Charge program is now open only to EVs, after initially accepting other alternative fuel vehicles. It has roughly 4,000 participants and a fee cap – that is, when owners hit a certain mileage mark, they will pay no more for the year. Drivers currently pay 1 cent per mile traveled.

- Virginia: The commonwealth’s Mileage Choice Program debuted in 2022 and has drawn more than 12,000 participants, far more than what officials expected. The system has a fee cap and is offered as an alternative to a highway use fee charged to owners of EVs and vehicles that get 25 MPG or better. An initial $15 is charged to start a driver’s balance and mileage fees are automatically deducted as they drive. Once the balance drops below $5 per vehicle, another $10 is automatically added to replenish the account.

- Connecticut: Effective Jan. 1, 2023, truck drivers in Connecticut must pay a highway use fee for every mile they operate within state lines. The fee is scaled to the weight of the truck, from 2.5 cents per mile for those weighing 26,000 to 28,000 pounds to 17.5 cents per mile for those weighing more than 80,000 pounds.

COUNTERING MISCONCEPTIONS

To become

To become a viable substitute for the gas tax, these limited programs will need to give way to full-scale, mandatory MBUFs that apply to all vehicles. For now, experts say a lack of public awareness of these systems has made policymakers nervous to implement them. Especially at a moment when political divisions are deep and misinformation is rampant online, it could be easy to attack such a major change as a “new tax” or an invasion of privacy.

However, data shows that once people learn about MBUFs, they come to regard it as a fairer system. New Jersey surveyed participants before and after its 2022 pilot project and saw declines in some of the most common reservations, including worries about data privacy (64 percent before to 34 percent after) and the accuracy of mileage charges (41 percent to 20 percent).

“Everything from privacy, to how annoying is it going to be, to is it accurate – every single concern across the board dropped,” said Reader, of the Eastern Transportation Coalition, which partnered with New Jersey on its pilot. “They didn’t go away – those concerns were still there – but the pilot really helped to alleviate some of them.”

One of the most common misconceptions about MBUFs is that they would disproportionately hurt rural drivers. The opposite appears to be true. An

Eastern Transportation Coalition analysis of their member states concluded that rural drivers on average would pay $34 less per year under an MBUF in Pennsylvania, $17 less in North Carolina and $9 less in Delaware.

“One of the questions I get most often is, is this going to hurt rural drivers? I tell people, I grew up in a town with 120 people in North Dakota,” Rohde said. “I always ask them, how many miles per gallon do you get in that pickup truck? It’s usually 10-12. And I say, you know, you’re paying the gas tax while the people in Fargo who are driving Teslas don’t pay anything. Is that fair? It’s amazing how fast people start to realize we’re in a system that is inequitable right now against people who are lower earners, because they’re usually driving older and less fuel-efficient cars, so they’re paying more.”

Karl Vilacoba is the Communications Director for the Monmouth University Urban Coast Institute.